The Immortal Calvin and Hobbes:

A Collection of Perspectives

into the Literary Legend

Michael Hundevad

University of Minnesota Crookston

Dr. Dani Johannesen

WRIT: 3994

4/29/2024

Table of Contents:

Abstract………………………………………………………….……3

- Introduction………………………………………………….4

- Sleigh Rides…………………………………….…….….….7

- Pedagogy……………………………………………….……11

- The Silence is Loud……………………………….………..15

- The Authoritative Bill Watterson.………………….……..19

- What’s to Come……………………………………….……..21

- Works Cited and Figure Reference Appendix….………24

Abstract

Writers, painters, and artists of all forms are under the scrutiny of their patrons influenced by the adage: write what you know. There’s a little truth, and in most artforms, artists use their livelihood and experiences as influences and muses for their artwork. Most plot lines and dialogue are reflections of that lived experience, yet Calvin and Hobbes is different because Watterson does not write what he knows, he writes what he doesn’t know. In the world of comic strips, where illustrations allow a deeper layer of storytelling, where the art can voice different messages than the text ever could, Calvin undergoes experiences that are universal, uniquely human, and emotionally warming.

Rather than solely finding a funny punchline, or an amusing tale, Watterson traverses’ multiple levels of philosophical, sociological, and metaphysical questions while delivering them in easy to digest, fun, engaging, and entertaining art filled panels. In this essay, I will dissect Calvin and Hobbes’ artwork, text, and influence through the perspectives of literary elements to determine why after thirty years since its finale, it remains not only a cultural touchstone to readers, but a literary legend. Due to its unique writing style, seamlessly living in varied artforms and timelines where imagination and realty co-exist, its philosophical grasp on existential questions, sociological inquiries into the follies of human nature and endless fun, Calvin and Hobbes will continue to shape the literary world of storytelling tactics, influence comic strip as an artform, and live on as a literary legend.

- Introduction

Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson. Ending new publications in 1995, itremains prominent in the literary world and the cultural zeitgeist, continuing to be referenced, influenced on, and circulated. It’s a comic strip that did not aim to be funny, it did not aim to reap rewards or money. It’s a story about a child growing up, and his parents learning too. It’s a story about the relationship between a family, the relationship between a child and a true friend, because despite Calvin’s world, Hobbes is real to us. The duo both speak to us, sometimes literally breaking the fourth wall.

Literary elements were numerously employed in the comic, it played with genre themes such as sci-fi with Spaceman Spiff, prehistoric worlds with Calvin as a T-Rex, worlds filled with magic, gravity-defying antics, and of course, aliens. Watterson played with artforms such as cubism, and detective noir storytelling as Calvin imagined himself as a hard-boiled private investigator. And Calvin’s cardboard box invention of “The Transmogrifier” allowed him to shapeshift into any physical being, (often opting for the elephant so he could memorize his homework) providing for endless creative fun on Watterson’s part, and numerous escapades for us to read. In Why Calvin and Hobbes is Great Literature, (2016) Gabrielle Bellot wrote:

Calvin and Hobbes feels so inventive because it is: the strips take us to new planets, to parodies of film noir, to the Cretaceous period, to encounters with aliens in American suburbs and bicycles coming to life and reality itself being revised into Cubist art. Calvin and Hobbes ponder whether or not life and art have any meaning—often while careening off the edge of a cliff on a wagon or sled.

The comic strip is not defined by one theme, character archetype, relationship, or direction. It’s also not bound by time, location, or current events, given Watterson never writes anything of note in Calvin’s world. This makes it able to be in any time, any place, and any reason. This variety in genre and artform allows Calvin and Hobbes its “immortality,” to transcend the barriers that typical comics are hindered with, forced to stay within their archetypes and formula for plot. While most comic strips struggle to stay relevant not only in popularity, but on bookshelves and in our minds, Watterson’s invention remains famous, often recited, referenced, and lives rent free in most people’s minds as a literary masterpiece from their childhood.

Nearly thirty years after Watterson’s last Calvin comic, why does it remain so popular? I argue because it’s in the same vein as Dickinson, Camus, Beckett, Frost, Rosseau, Emerson, and the like. They not only write well, they write about the well-being of humanity, our Sisyphus-ian nature, our humorous antics that make us absurd, and the follies of society and group-think. They write about what they don’t know, but how they react to it anyway, the epitome of sociology. Watterson experiments with these social sciences in the fun-sized artwork of a sugar-induced child, mixed with some literary genius, he crafts the immortal Calvin and Hobbes.

Calvin and Hobbes gives readers an easy introduction to philosophy, sociology, and science. Not only is it funny and entertaining, it is not informative at all about the actual science and ways of the world. It poses the questions every person at every time has asked themselves and never gives them the answers. And while Calvin feels alone in the backdrop of the darkness of the cosmos as he screamed for the void to answer him back, we all feel that loneliness with him, and in that, we don’t feel as alone. Or at least we’re comforted by the morbid fact that everyone feels this way. And we the reader become attached to Calvin, his mind, and his antics, because we relate to Calvin not by a joke, but by his human nature, which we all intrinsically share. The same way Dickinson enamored the world and Camus shocked it, Calvin won us over. Maybe not most importantly, but most prominently, is when reading Calvin and Hobbes people see and react to the wild imagination and raw intelligence that Calvin has, and we admire him for that. And yes, they are just plain fun to read.

The illustrations are vivid, creative, and grandiose in Calvin’s imagination, but share with the reader a deeper and more elaborate story and message than the text and dialogue ever could. The quips are funny, the situations are laughable, and the stories of Spaceman Spiff are whimsically thrilling. We’re always supporting and cheering Calvin on, while walking alongside him as he discovers life’s consequences, the way of the world, and the absurdity of it all.

| Figure 2 |

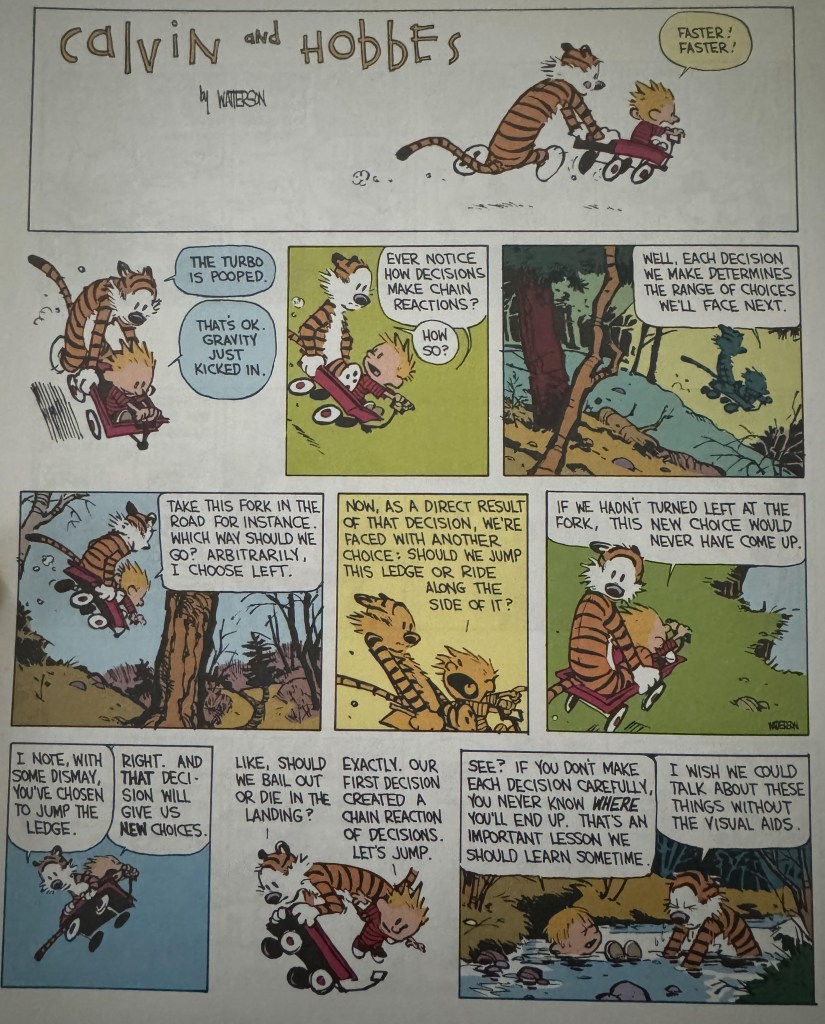

II. Sleigh Rides

I recently was re-introduced to Waiting for Godot, and I can’t help but relate some of the characters to Calvin and Hobbes. Vladimir and Estrogen are obviously Calvin and Hobbes, though which one is which I am not sure. That doesn’t make the dad and mom Lucky and the other guy, although I could relate the dad to Lucky more than I could anybody else. Valdimir and Estrogen say to each other to go see Godot many times yet stay put. Calvin and Hobbes in their wagon ask what it means to act on decisions and the impact, if at all, on those choices, while moving at a rapid dangerous pace with good airtime. They relate in similar tones, but opposite actions. The irony is asking if decisions matter as you hurl down a steep hillside at neck-breaking speeds on a toy wagon, the irony is Godot’s crew asking to go make your own fate and meet your own plans and overcome your own obstacles yet remain still and motionless.

Bill Irwin, an accomplished American actor and clown who has embodied the character Lucky in Waiting for Godot numerous times, discussed this in his one man show On Beckett at the Guthrie Theatre in 2024 as “body and soul detachment.” Irwin references how every character in Beckett’s play at one point says one thing but exhibits the complete opposite nature in their physicality. “Thoughts versus action abrasions,” (Irwin, 2024). Calvin the deep thinker, is not an adrenaline junkie, but a moment (by moment) character coming to age, literally, and metaphorically. While his body is experiencing one thing, his mind is elsewhere experiencing another. This is common in Calvin’s world; another example is him frequently getting lost in his daydreams as Spaceman Spiff while sitting quietly in school.

The juxtaposition of a kid barreling down a death-defying hill in a rickety old wagon contemplating fate and freewill is a funny situation coming from a six-year-old who seemingly has “his whole life ahead of him.” That is what makes it entertaining and engaging, but not necessarily relatable or poignant. What makes it poignant is the universal human experience of all of us asking these questions. And that is supported by the millennia of philosophers from Ancient Greece to modern day philosophers like Camus, Thoreau, and Thomas Hobbes, asking the same questions in different forms: why are we here? What’s it all for? Does it mean anything? Do my decisions matter? These questions and arguments are scrutinized more seriously when it’s an educated adult writing a dissertation, often ignored, heavily judged, or even dismissed altogether. In the medium of Calvin and Hobbes, it breaks the conventions of that “academia” stuffiness and monotony, and brings the same questions, thoughts, concerns, and existential comments into an easy, engaging, fun, and relatable read. The connection Calvin and Hobbes made with its fanbase, the world, and literature, is its humanness.

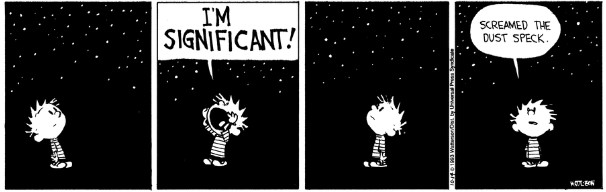

That is what makes Calvin and Hobbes so successful, intimate, and timeless; it is a window into the soul of not only childhood, curiosity, and imagination, but big French doors opening up cultural and sociological questions about human relationships, (parents, friends, crushes) our relationship to the skies, (heaven, death, the beyond) and our relationship to ourselves. The humor is in the absurdity of it all, and there lies the philosophical nature of Calvin and Hobbes (and Beckett) balancing perfectly a robustly absurd question with equally whimsical childlike behaviors. An academic blogger, Rudolph.58, (2016) wrote a lengthy analysis of Calvin and Hobbes in this same topic speaking about Figure 1, the strip of Calvin screaming he’s significant into the void:

“The comic strip provides a look into the human condition and the desire for meaning contrasted against a vast, unanswering universe. This closely resembles Camus’s description of the absurdity of the universe. Calvin is seen calling out to the universe, a notion that could stand for humankinds’ search for meaning. The universe, however, does not answer. This causes a crisis for Calvin, as Camus stated it would for many people, as he now compares himself to the meaningless speck of dust.”

Calvin, I would argue, does not fall into this crisis, more so than just realizing it, and allowing that to soak into his existence, just as we all did when we came to that epiphany in life as a child. However, Camus’s point stands, that it does cause a crisis for many people, and this is the cause for that outlook people take, that “stepping back” to look at the bigger picture. When the bigger picture is looked at, our lives don’t seem as trivial or complicated and are reminded of how lucky we are. However, it brings those questions of existentialism. To prove Camus’s absurdity right again, “despite this overwhelming feeling from stepping back, we just go on with life and still take it seriously,” (Rudolph.58, 2016). That is the absurdity of existence, and Calvin’s comic captures the concept candidly.

Calvin and Hobbes are young adventurers, philosophers, and thinkers. Calvin, given the proper guidance (who knows, I’m just speculating) would be a very good modern philosopher and probably would get a kick out of podcasting and all the streaming services. His prankster ways and ethical dilemmas give him the insight to be a deep thinker and truly understand complex topics, while having a fountain of wisdom and caution with vulnerability, society, and human relations. It is not a caution stemming from fear, but of scrutiny: curiosity and contemplation. It is those characteristics the reader experiences with Calvin and make a big contribution to Calvin’s likeability. He isn’t a two-dimensional character, he is not formulated to act a certain way, while he may be predictable, Calvin often surprises us, and that creates a stronger bond between the reader and Calvin.

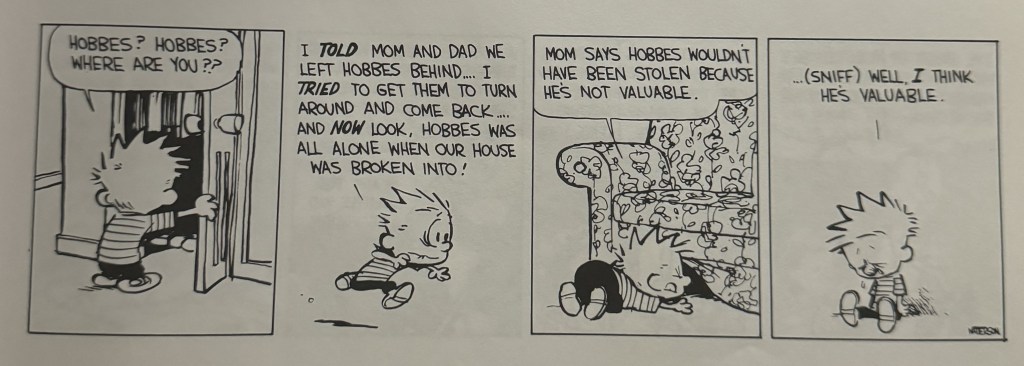

Watterson also does not shy away from going the other way in comic storytelling. The ‘funnies’ are taken seriously in the comic’s world, especially during the popularity of newspaper comics in the 80s and 90s. Yet, the funnies are never serious in text; they’re designed, fabricated, and edited to be humorous, and that’s the point. However, Watterson, for whatever reason of his own, never shied away from creating heartfelt moments, tender moments, or even just plain sad moments. There are few comparable comics that could be argued for this case; Schultz’s Charlie Brown, where the protagonist has it rough and tough, but it doesn’t and never portrays as genuinely sad because the audience is set up to laugh at Charlie Brown, and that is supposed to be the punchline. We are laughing mostly at Charlie Brown rather than with him, Lucy’s classic football kick fake-out for example. In Calvin and Hobbes, the audience is set up to care for the characters, which makes it more evocative and emotional when Calvin is genuinely scared, hurt, or feeling guilty.

In our world, few, if any, have had the Charlie Brown experience, but nearly everyone has been in the shoes of both Calvin and of his parents, where we have both have been the one who hurt and the one who has been hurt, intentionally or not. This is a universal human experience and Watterson captures those moments brilliantly, successfully articulating them to the readers through someone who is actually growing up, just like we, the readers, were and continue to do. This could be another reason why Calvin and Hobbes remain in the zeitgeist today, the connection between reader and character formed a strong bond, and they grew up together.

Calvin and Hobbes go another layer deeper with these elements; as most comics have an external conflict be the cause for the plot and joke, (Charlie Brown being faked out by Lucy’s football antics, Dennis being a menace to his neighbor, Archie’s high school drama, Tintin battling pirates or escaping boobytrapped tombs) Calvin is often wrestling with internal conflicts, dialogue, and his own self as the obstacle. Again, Watterson juxtaposes the seriousness of maturity with the whimsy of a child. Having existential arguments as if you are Hamlet as a six-year-old is absurd, making it funny, and therefore relatable by its innocence, ease of access, and simplicity. This simplicity is what allowed Watterson to project his perspectives on society, its follies, and unique philosophical takes from the panels of a comic strip. He extrapolated this medium in which to teach, explore, expand on, and investigate these philosophical quandaries. Bill Watterson in an interview with author and journalist J. Katzmarzik (2019) said, “if you sat down and wrote a two-hundred-page book called My Big Thoughts on Life, no one would read it. But if you stick those same thoughts in a comic strip and wrap them in a little joke that takes five seconds to read, now you’re talking to millions.” A scripture in comic strips. An exploration and commentary “to pick up and discuss various social, political, and cultural topics…on the conditio humana,” (Katzmarzik, 2019). Calvin’s own personal pedagogy.

- Pedagogy

Calvin is a first-grade student in Mrs. Wormwood’s class. Watterson also portrays him as a student in the metaphorical sense – a student of life. Calvin is constantly learning and scrutinizing how it works, how it functions, the consequences both good and bad from actions that he takes, something all humans can certainly relate to. The theme of learning, and relearning, is universal and an eternal human experience, another element that contributes to Calvin and Hobbes’ longevity and popularity.

Calvin and Hobbes is layered with a façade of childlike naivety, but that childlike innocence is what makes the reader connect to the characters and the nuances of the comic in a more profound way. The childlike nature of thinking about how to use the umbrella in the exact opposite way is a perfect example, and that childlike nature is rediscovered, reengaged, and relearned as an adult reader. It’s a reteaching of how to be childlike, in imagination, in thought, and in questions. The nature of exploring just for the sake of going. This way of life is an art and science in it of itself. Calvin in his learnings is reteaching them to the audience, in a new and whimsical light. In Watterson’s panels, it’s more than an exploration of philosophy, it’s a deep look into the nature of learning and teaching through the mind and play of a child. The immortality of Calvin and Hobbes directly stems from that eclectic and miraculous mind of childhood – from the gifts of play.

When a child plays, they are exploring. When a person is learning, they are exploring the rich details, facts, and analyses of that topic. When a person explores their thoughts, feelings, and the world around them, they learn. Exploring is a theme prominent in Calvin and Hobbes and while its surface layer is meant to be a child exploring the world through play, its deeper layer is of exploring those gifts of philosophy, life, and the relationship with one’s self.

Calvin is wholly independent. Calvin has no other leading characters like that in The Peanuts or Dennis the Menace, or Tintin. Calvin is the main source of his own entertainment. Entertaining oneself via imagination and antics is a child’s way. Calvin being alone and in solitude is another avenue that allows Watterson to explore any and all topics with no pressure to write lines for other characters or have dialogue be the main driving force. Watterson was free to monologue.

Michelle Abate in her article A Gorgeous Waste: Solitude in Calvin and Hobbes, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, writes from interviewing Watterson, “Calvin and Hobbes has long been seen as a comic about friendship. I agree, but with an important modification: Watterson’s strip is about the relationship that we can have with ourselves when we are by ourselves,” (2019, p. 502). Calvin is almost in solitude the entire time. While Hobbes is there, it is really Calvin and his own mind and imagination. And that comfort and purpose one must give to oneself is a completely universal human suffering that not many comics, nor novels, have been able to portray as efficiently and as whimsically as Calvin and Hobbes.

John Calvin, the philosopher, was a significant leader in the Protestant faith. A tenet of Calvinism is that a relationship with God is a relationship with oneself and that predeterminism is a dominant force in life. “In recognizing God as the source of one’s being, one found true purpose,” (Mark, 2022). This is a relationship with the self, with solitude, and with one’s own core values. John Calvin defines Christianity as a personal relationship with God because God is the source of one’s life, one’s actions, and one’s comfort, (Mark, 2022) and when you nurture that relationship, you nurture your purpose.

Thomas Hobbes is famous for saying that life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” (Munro, 2024). Not much different than the actual livelihoods of literal tigers. In Hobbes’ State of Nature, he states the social contract is not a political treaty between people, but a principle based on self-preservation. Hobbes said, “each individual has a natural right to everything, regardless of the interest of others,” (Munro, 2024). Hobbes says life is violent and brutish because humans are violent and brutish, our pursuit to own, control or perpetuate an ideal ‘‘regardless of the interests of others,” (Munro, 2024) is what drives our conflicts. “In short, their passions magnify the value they place on their own interest, especially their near-term interests,” (Sorell, 2024). Hobbes’ philosophy is that humans focus on the short-term tangible lifestyle, whereas Calvinism focuses on a person’s spirit and their afterlife. We can visualize these two philosophies as vertical and horizontal; Calvin’s ideals are vertical where the person should focus on the higher power and afterlife, and Hobbes’ ideals are horizontal, focusing on personal ideals through social contracts and short-term interests.

Watterson naming his dynamic duo after two vastly differing philosophers is him writing his “Big Thoughts on Life.” While paying homage to the philosophers and relating their perspectives into the personalities of the characters, Watterson is more prominently poking fun at the stuffiness and high-brow society of philosophy and brings it back down to earth, back down to childhood. At the time of Watterson’s publications, in the 80s and 90s, there was a shift in cultural thought. “It was an age between the beginning of post-Christian secularized worldview of the sixties and the radicalism of the twenty-first century’s New Atheism,” (Katzmarzik, 2019). Watterson parodies postmodern ethics with Calvin the character by exhibiting the ideals of Calvinism – “he fully embraces the concept of predestination, but only to disclaim any personal responsibility,” (Katzmarzik, 2019). It’s a vertical relationship with Calvin, and Watterson pokes fun at it by having Calvin be the extreme devil’s advocate and exploring those ideas as a modern suburban kid.

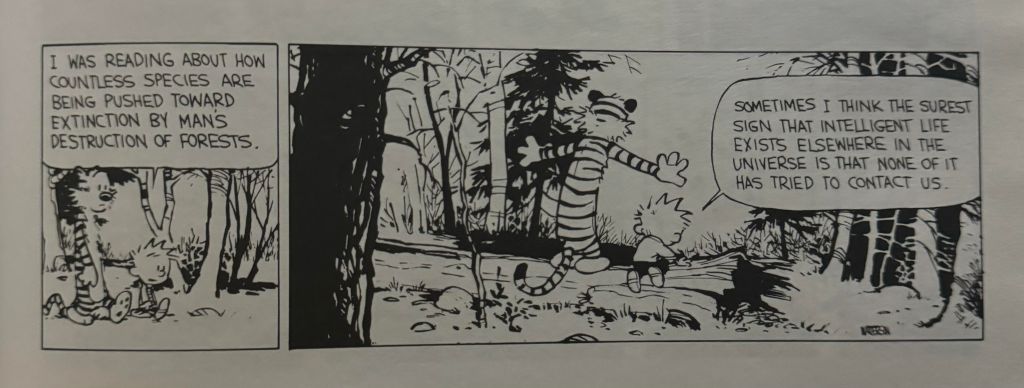

Hobbes on the other hand, both the philosopher and the stuffed tiger, take the horizontal philosophical look on human nature – person to person relationships. Hobbes, the tiger, often laconically claps back at Calvin when asked ethical and moral questions, representing both Watterson’s parody of postmodernism and the fallacy of the pedagogy of John Calvin. In figure four, Watterson crafts a humorous take on the relationship between self (Calvinism) and the relationship between people (Hobbes). Both characters correctly represent their respective philosopher and their ideas, yet when set side by side and through the eyes of a suburban kid, all valid points and seriousness is mooted. It does not diminish the importance of the exploration of such a question, but simply and humorously comes full circle to the absurdity of it all.

The vast contrasts between each, and the way cultural identity shifts over time, Watterson observes that it creates existentialism and only emphasizes the follies of life. Especially when the reader steps back and thinks about Hobbes being a stuffed tiger, it would be Calvin both asking this question and answering it, giving opposing opinions: the duality of man.

Watterson undermines and scrutinizes this seriousness. From a pedagogical perspective, if a person’s life is already predetermined according to John Calvin, then they cannot be held responsible to change their actions and morals. According to Hobbes, if the only thing keeping the peace between people is that social contract of self-interest and preservation, that means that people’s actions and ethics are based on a morality of behavior, whereas Calvin says it’s a morality of theology.

Calvin the character is of no faith however, never proclaiming or even administering Christian beliefs into the comic. This resonates with the cultural shift of Christianity into that post-modern atheism. Calvin’s moral compass is based off his short-term interests, much like a true American child. Through toys, Santa, and other childlike rationalities, the idea of being good is only there to fulfill self-interest. Watterson explores these philosophies and pedagogies though the morality of his life experiences and scrutinizes the absurdity of such tenets.

In one comic, Calvin asks Hobbes, “Do you think babies are born sinful?” (Watterson, 1992). This inquiry is ultimately the basis of Calvinism, if all life is predetermined, then the sins done by man are not to be surprising, maybe even expected. Hobbes, however, plays the profound devil’s advocate, instilling on human behaviors he experiences into quirky dialogue. Hobbes replies to Calvin, “I think our actions SHOW what’s in our hearts.” Katzmarzik (2019) scrutinizes this by saying “Hobbes’s reply reveals his conviction that one’s deeds are a mirror of one’s character. A person does not merely do a bad thing, but the bad deed is an indicator of the deprived human nature and the state of man,” (p 194). And that reply is Thomas Hobbes in a nutshell, that life is violent and brutish because the deprivation of the fulfillment of human desires leads to dissent. Fate and free will, a morality of behavior or morality of theocracy, either way, both are never answered, and never will be. To Watterson, both are absurd foundations.

| Figure 5 |

The Silence is Loud

Many of Watterson’s strips don’t end with a tried-and-true punchline, but rather an illustrative reaction from the characters that act as the punchline. In these strips with silence, Watterson breaks the traditional trope of having dialogue be the driving force of the comic strip. The illustration speaks louder than words, after all if a picture is worth a thousand words already, is a picture with words worth more?

This tactic is not new at all, and in the history of comics, both strips and political cartoons, a lack of dialogue is commonplace, but usually in place of banners, suggestive titles, and evocative background texts or labels. So, the use of words is still prevalent, emphasizing and hyperbolizing the given illustration. In Calvin and Hobbes, the lack of words requires that the illustration is not hyperbolized, not melodramatic, and not confusing. This requires specificity in the illustration but also the execution of meaning and message without words. Not many comics have done this, and fewer have been included into the funny pages.

Watterson flexes the artform of comic strips and exercises the playfulness of silence, the nuanced communication it can achieve, and therefore takes advantage of. Perhaps this is another reason Calvin and Hobbes struck a certain chord with the culture that fell in love with it; the variety of storytelling, the minute details, and varied interpretations create that sense of intimate connection, that Calvin, Hobbes, the mom and dad, all share the same sentiment, questions, and quirky life experiences that we do. But it goes beyond that, because all art reflects life, and certainly the Sunday funnies are no different. They often aim to be current and up to date, however Calvin and Hobbes transcends that barrier because it transcends current events.

Calvin and Hobbes was written to be in any time, because it never adhered to time, current events, or world happenings. It all was just the experience of a boy growing up and left out everything else. This made it relatable, it allowed the suspension of disbelief to be completely dropped, and the notion and care and opinions and even the thoughts of anything worldly or outside of Calvin’s universe to not exist, to not be troubled with, and to not be worth thinking about. It freed the readers into a form of escapism which certainly led to Watterson’s primary success, but also led to the comic’s longevity. Calvin and Hobbes therefore is never going to be “out-of-date”, never to go out of style, and never become old.

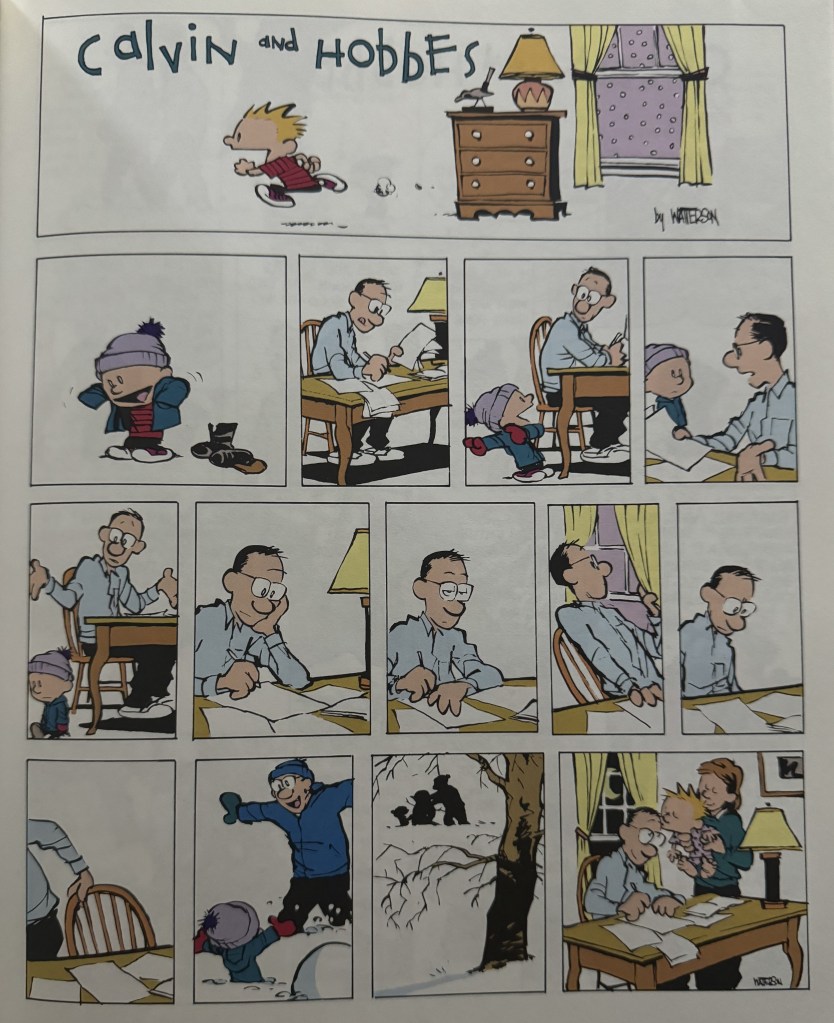

Calvin surprises us. Not every comic Watterson made was a punchline, not everything had to be funny. This again is a literary element in his storytelling that elevates this comic above all others with its sincerity, its humanness, and its heartfelt moments. Comic figure six is completely silent. Watterson takes an entire Sunday strip and says nothing, it has no joke, and it is one of the most famous strips of his. Why? In all the other absurdities and antics Calvin has asked and gotten into, the love of father and son transcends all humor.

Other silent comics of Watterson’s take different aims, the humorous, the contemplative, and the absurd. Again, because it’s through the shenanigans of a six-year-old, words and text are often not needed because of the actions that Calvin gets out acts as the bit. Figure seven shows Calvin playing with his food then getting punished for it by his mother. Watterson is not showing that the disciplinary consequence Calvin receives is the punchline, but it’s the consequence of one’s actions that receives the introspective humor. The illustrations are loud despite there being no dialogue amongst the characters. For Watterson, silence is a tool used to speak out against these human conditions. For Calvin, he is just playing, using his imagination, and is doing no harm to anybody else, so why then is his behavior being punished, why is it seen as bad? Well, it’s not bad in the moral sense, just bad in a societal sense, that playing with food is considered rude. That rudeness, however, is a cultural phenomenon, a social norm imposed by society. Watterson scrutinizes this, as he does with all philosophical takes, and turns the pedagogy of bad and good behavior into a showcase of humorous absurdity.

Silence in literature is only possible with pictures. Comic strips use literary elements, but the element of silence can really be emphasized with comic strips using those illustrations. In Calvin’s world, the food is alive, moving, and sentient. Through pictures only, we see a full storyline of exposition, conflict, and resolution. And the resolution is funny, real, or sad depending on which Calvin comic by Watterson we scrutinize. It’s a literature that then transforms storytelling from a medium of having text be a means of communicating ideas, to having pictures be the means of communication. Silence is therefore an element in literary storytelling, and where silence can dominant, then literature can expand the ideas of what communication actually is. Just as different interpretations can happen from the same text, even more interpretations can be explored through the means of silence.

Through the medium of comic art, an author can expand on the meaning of it by having those two differing mediums interact and sometimes even juxtapose each other. The illustrations become just as important, if not more, than the dialogue because it also tells a story. From an interview with Bill Watterson:

“The illustrations in Calvin and Hobbes [are] the fantasies are drawn more realistically than reality, since that says a lot about what is going on in Calvin’s head. Only one reality in Calvin and Hobbes is drawn with a level detail comparable to the scenes of Calvin’s imagination: the natural world. The woods, the streams, the snowy hills the friends careen off the natural world is a space as enchanted and real as Hobbes himself,” (McEvoy, 2023).

The enchantment is simply the mind of a child. The world is filled with more grandeur and grandiosity in both the creative lens, and in the natural world for a child. The fantasies becoming real is that escapism what first drew people into the comic, and the pedagogical approach to absurd philosophy mixed with absurd humor struck that chord with people that made them stick around. The immortality of Calvin and Hobbes directly stems from that immortal, ethereal, and miraculous energy of childhood, of “the gifts of play, of the inner life, of imagining something other than what is there,” (McEvoy, 2023).

- The Authoritative Bill Watterson

Four anthologies, numerous more strips, and a decade of being published in the papers, Calvin and Hobbes helped shape and define a generation of readers, imagineers, kids and adults alike. The duo swept culture off their feet. The syndicate is forever immortalized in the American zeitgeist, but how much impact did it really have on literacy, literature, and culture. No other comic has so much variety in style, art, narrative structure, and writing styles, (McEvoy, 2023). From the forward poems to headliner comics, the characters are much more than fiction, they very much so are real parts of all of us.

In December 1995, the last Calvin and Hobbes comic was published (McEvoy, 2023). It came as a surprise to the fan-base, and an outcry poured out. After a decade of building up the momentum of its popularity, it ended. Watterson reflects that if he were to continue, the audience that so liked him before would get bored of him, and the charm would soon wear off after Watterson saturated it, and lost ideas. From the McEvoy (2023) interview, Watterson states:

“If I had rolled along with the strip’s popularity and repeated myself for another five, 10 or 20 years, the people now ‘grieving’ for Calvin and Hobbes would be wishing me dead and cursing newspapers for running tedious, ancient strips like mine instead of acquiring fresher, livelier talent. And I’d be agreeing with them.”

The allure and longevity of the comic is due to its seemingly rare appearance. While it is not inhibited or hindered in sales or business, or even in literary circles, it created its own success and maintained it by solely being a work of art in a comic strip. Watterson alludes that if the comic strip had been merchandized, it would have lost its gravitas to the public. Just as milking the comic for more years in the newspaper would have done, selling the intellectual rights to be merchandized would have diminished the literary genius that is Calvin and Hobbes.

Unlike The Peanuts and Dennis the Menace, there were no plush toys, movies, or cartoons that other marketing syndicates took advantage of. In Watterson’s words from above, it would have diminished the concept of Calvin and the efficient efforts of Hobbes. It would have made the parents mundane, the adventures of Calvin boring, and the laconic expressions of Hobbes produce a yawn rather than a chuckle. Watterson states, “if I’d wanted to sell plush garbage, I’d have gone to work as a carny,” (McEvoy, 2023). And that decision only magnified and made the duo more coveted. To the syndicate, the comic was a way to make money, for cultural icons to be produced and manufactured, sold, and profited from. To Watterson, it was just a story of a kid growing up, and a way for the author to explore cultural and moral values in a fun and easy way. Watterson didn’t want to “sell plush garbage,” he wanted to speak. And in the ten-year time, the speaking came to a fruitful and organic end, that Watterson felt was right.

Watterson decided it was time to move on, to go exploring his other life choices and opportunities, to go draw on a fresh sheet of paper. I think it’s what Calvin would have wanted for him, too. And that’s another theme taken to heart from the strip, being comfortable in oneself with the decision one makes; not something any literary comic strip can achieve.

- What’s to Come? Conclusion or Carrying On

As newspapers declined and the internet took hold, comics transformed into the medium we all encounter, enjoy, and have become synonymous with internet culture: memes. Comics in newspapers are the precursor to memes and internet comics. Comics still exist in the form of hard literature, i.e. graphic novels, comic strip anthologies in print, etc., and comics still exist in newspapers today, but the fact that newspaper print is in decline ultimately led to the decline of comic strip readership as well. The medium and artform however, perhaps with the advantage of being a forefront of entertainment for late millennials and early Gen Z’ers, thrived and evolved from paper to the internet just as we did because it’s familiar, it’s easy, it’s fun, and it’s relatable. Memes of multiple panels to single panel formats, and long form meme comics have all the same technical aspects of traditional comic strip making. It’s art and text combined to create these jokes. So, the future of comics is not dismal, in decline, or on the fall, rather more like a cultural literary movement like from classical to the romantic period, the comics format is simply evolving from a post-modern to a more contemporary period.

Calvin and Hobbes has many influences either by design or by coincidence. A great example is the Hulu show Wilfred, starring Elijah Wood. Elijah Wood plays a human while his co-star plays a dog, in a dog costume. Elijah is the only one who sees Wilfred as a talking, bipedal, humanoid dog, and is the only one who holds conversations with him. Everyone else sees Wilfred as a literal dog. The duo partakes in recreational drugs and alcohol alongside their existential and somewhat illogical antics, in order to provide insight and wisdom into Elijah’s journey to become a better person. This is a direct descendant (and possibly in a certain timeline, the adult version) of Calvin and Hobbes. The philosophical banter and enlightenments, the sarcastic, laconic remarks, and the friendship that bonded this unlikely duo together captured audiences, brings solace, humor, and an appreciation for both the follies and the faults of life that make it so perfectly funny. From this perspective, it is Calvin and Hobbes reincarnated.

Wilfred is a show about a person needing to grow up, relearn personal values, and the way of the world. A person and his dog take on the large philosophical quandaries just as the cartoon duo do. So, while the cartoon is decommissioned, its influences over media, art, film, and literature live on and are expanded upon by the very culture that grew up with Watterson’s creative comics. Watterson himself, has never stopped making literature. His explorations never ceased, and the lessons and curiosity that Calvin taught to its readers is showing up time and time again in media, art, and literature.

Watterson has a new book that was published in October 2023. Titled The Mysteries, it is aforty-three sentenced short story that is quick witted and takes place in the fantasy world of knights, dragons, castles, and a charming protagonist. According to McEvoy, (2023) it reflects the same nuanced storytelling that Calvin and Hobbes achieved and executed so well. Like in true graphic novel fashion, and therefore comic strip fashion, the illustrations and the text are paired, emphasizing, and supporting each other, but independently tell very different stories and utilize storytelling in different ways. “The illustrations,” talking about Watterson’s 2023 The Mysteries, “are slower to process, and do much of the storytelling work,” (McEvoy 2023). Watterson’s style of storytelling lives on then, and even though there are no new Calvin comics, it is reassuring and comforting to know the same pedagogy, philosophy of sleigh rides, and use of illustrations in this literary artform live on, and carry with them the tenets of the Calvin and Hobbes.

Figure 8 is Watterson’s last published Calvin and Hobbes strip from December 31, 1995. With this knowledge it paints a different picture of Hobbes and Calvin going off to explore, of Watterson leaving the syndicate, and what their endings mean. For Watterson, it was just time, leaving with no regrets, saying “he had done all he could with Calvin and Hobbes,” (McEvoy, 2023).Watterson decided it was time to move on, to go exploring his other life choices and opportunities. Watterson leaving Calvin and Hobbes is like a child growing up and moving on to the bigger world. It’s bittersweet, and we cannot be mad at Calvin, for we always supported, encouraged, and befriended him and his stuffed tiger. And we can only do the same for Bill Watterson, and all literary artforms.

Calvin and Hobbes is a literary legend. 30 years after its last comic, it remains one of the most referenced and known comic strips of all time. Its influences reach beyond the page and dip into film, television, novels, music and even stand-up bits, (rudoplh.58, 2016). With its philosophical takes and funny takes on the follies of life, it created a world where people could be entertained, and educated; it provided a sense of intelligence mixed with humor. A smart person may be able to read Calvin and Hobbes and dissect it and analyze it through different literary and philosophical perspectives to provide a dissertation about its influential artform and storytelling, but a genius just takes those philosophies and writes jokes about them, making it as easy as a kid thinking about them. Bill Watterson is that genius, and Calvin and Hobbes is that literary legend.

References

Abate, M. (2019). “A Gorgeous waste”: Solitude in Calvin and Hobbes, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 10:5-6, 488-504, DOI: 10.1080/21504857.2018.1523204. “A Gorgeous waste”: solitude in Calvin and Hobbes (umcrookston.edu)

Bellot, G. (2016, July 18). Why Calvin and Hobbes is great Literature: On the Ontology of a Stuffed tiger and Finding the Whole World in a Comic. Literary Hub. Why Calvin and Hobbes is Great Literature ‹ Literary Hub (lithub.com)

Irwin, B. (2024). “On Beckett.” Guthrie Theatre. Produced by Todd Hartman. Created by Bill Irwin.

Katzmarzik, J. (2019). Comic Art and Avant-Garde : Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes and The Art of American Newspaper Comic Strips. Universitätsverlag Winter. Comic art and avant-garde : Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes and the art of American newspaper comic strips – University of Minnesota (umn.edu).

Mark, J. (2022, Mar. 16). John Calvin. World History Encyclopedia.

McEvoy, C. (2023, Oct. 10). Bill Watterson. Biography.com. Bill Watterson: Biography, Cartoonist, Calvin and Hobbes Creator

Munro, A. (2024, March 28). State of Nature. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/state-of-nature-political-theory

Rudolph.58. (April 22, 2016). Tomorrow Always Comes, and Today is Never Yesterday. The Ohio State University.Tomorrow always comes, and today is never yesterday. ~S.A. Sachs | Just another u.osu.edu site

Sorell, T. (2024, January 26). Thomas Hobbes. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Watterson, B. (1990). The Authoritative Calvin and Hobbes. Andrews and McMeel.

Figure 1.

Watterson, B. (1993). The Days are Just Packed. Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Figure 2, 6, 7, & 8.

Watterson, B. (1988). The Essential Calvin and Hobbes. Andrews and McMeel.

Figure 3 & 5.

Watterson, B. (1992). The Indispensable Calvin and Hobbes. Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Figure 4.

Zuckerman, D. (2011). Wilfred. FX.

Leave a comment